Archives for Healthcare Policy (page 1 / 4)

September 21, 2015 09:35 AM

By Joe Martin in Politics

Andrew Pollack wrote a shocking expose of corporate greed, revealing that Turing Pharmaceuticals jacked the price of Daraprim from $13.50 a tablet to $750 a tablet. This is a 62-year old drug.

Pollack spent 21 paragraphs writing about the importance of this drug and the shockingly unapologetic greed demonstrated by Turing Pharmaceuticals. I spent 21 paragraphs wondering how a company could increase the price of an unpatented drug by 5,500% without being undercut by a competitor.

In paragraph #22, Pollack finally decided to toss off a few sentences about that.

With the price now high, other companies could conceivably make generic copies, since patents have long expired. One factor that could discourage that option is that Daraprim’s distribution is now tightly controlled, making it harder for generic companies to get the samples they need for the required testing.

Oh-ho. It's government regulation. Manufacturers of generics need to compare their own prototype pills to Daraprim, before they can get government permission to market and sell a generic. Prescription laws make it hard to obtain Daraprim without a prescription and Turing's control over its own supply chain ensures that nothing leaks out. In essence, government restrictions on trade are giving Turing a monopoly on a patent free drug. Turing's price hike would be impossible without this government protection.

The New York Times article frames this as an issue of greed. But greed is a universal constant. It's always with us. Greed is never an explanation for unpleasant behavior. The real question is why nothing is acting as a check on greed. In this case, the government is blocking that market based check. I can see two solutions.

- Stop restricting access to pharmaceuticals. If the FDA didn't tightly control drug distribution, generic manufacturers could easily obtain their own supply of Daraprim and start cranking out much cheaper copies. Turing would be forced to lower their prices to match and greed would be kept in check.

- If you are going to restrict access to pharmaceuticals, there should be an exception in the law that allows generic manufacturers to easily obtain access to the main drug, for the purposes of cloning it. I see no good reason to give Turing Pharmaceuticals a government enforced monopoly on the drug's distribution and supply once the patent protections have expired.

Once again, the New York Times has made the free market into the villain of the piece. I think the real villain is the government restrictions that give Turing Pharmaceuticals power it doesn't need and shouldn't have.

June 15, 2015 06:28 AM

By Joe Martin in Politics

The biggest problem in healthcare is that providers—doctors and hospitals—are allergic to straightforward pricing and refuse to give actual prices before providing services. This idea for a solution isn't perfect but I think it's worth trying.

Perhaps a solution in the healthcare arena would be to institute binding arbitration in cases where providers refuse to agree on prices before providing service. And perhaps the binding arbitration could be based on the fee the patient offered to pay upfront, but declined by the provider in favor of bureaucratic claims processing. For example, if a patient had offered (in good faith) to pay $5,000 for the surgery; but the EOB and claim came in at $50,000, the arbitrator would award one or the other. Common sense tells us that the arbitrator will almost always award the patient’s upfront offer.

∞

February 26, 2015 06:49 AM

By Joe Martin in That's Interesting

David Henderson shares this story, from LCDR Ilia K. Ermoshkin, an officer in the U.S. Navy.

I grew up in the USSR and became familiar with the healthcare system both from the beneficiary point of view and from that of a provider, as my grandmother was a dentist. The government owned and ran all health care, and it was free to the people. However, the quality and the "care" in the health care system were dismal: long waits for specialists and advanced procedures, etc. But, as anywhere, people have developed ways to get around and get what they want. Here are some examples of wonderful free health care in the USSR.

Birth was to take place only at birth clinics, of which there were about half a dozen in a city of five million people. Husbands or any other family are not permitted to even enter, under the premise of keeping the place free of germs, etc. My delivery was very difficult for my mother, she was in labor for three days, and it was deemed unnecessary to give her any pain medication or do a Cesarean. So she roamed the hallways of this clinic/hospital howling with pain. Nobody was permitted to use the phone (there were only a few in the administrative offices), so she could see my father and her parents only through a window once a day. When I was finally born, I was taken away from my mother immediately to be placed in a post-birth unit (this was done to all newborns), and my mother did not see me until about 24 hours later. We were released from the hospital after 7 days, and that was the first time my father saw me. This is a story that was a fairly normal routine for the Soviet women, and no other options were available as it would be then nearly impossible to get a birth certificate for the newborn. When my mother told this to my wife, who is American, she was horrified and had nightmares about it. [DRH note: for similar stories about the birth process, see Red Plenty. I reviewed it here.]

When I was two, I got severe pneumonia. I was at home with fever of 42C [DRH note: this is over 107 degrees Fahrenheit] and the doctor decided that this was a lost case and would not even prescribe penicillin to try to fight the disease. It took my parents and grandparents pulling all their connections and bribing to get penicillin that fairly promptly took effect and saved me.

∞

February 25, 2015 07:24 AM

By Joe Martin in Politics

Thanks to government policy, the word insurance has been fatally corrupted in the health care industry. Insurance arose as a way for groups of individuals to protect themselves against insolvency by pooling their risk of unlikely but highly costly happenings. Today, private and government health insurance is merely a scheme to have others—the taxpayers or other policyholders—pay one’s bills not only for rare but catastrophic events, but also for predictable and likely, that is, uninsurable, events—and even for goods and services used in freely chosen activities.

The system is so camouflaged that the privately insured are often simply prepaying for future consumption, but the prepayment includes a hefty administrative overhead charge, which means the policy would be a bad deal if customers were paying the full price with eyes open.

What makes private medical insurance look like a good deal today is that employers seem to provide it for "free" (or at low cost) as noncash compensation, or a fringe benefit, which is treated more favorably by the tax system than cash compensation. If an employer pays workers in part with a $5,000 policy, they get a policy that costs $5,000. But if the employer pays workers $5,000 in cash, they’ll have something less than $5,000 with which to buy insurance (or anything else) after the government finishes with them. That gives employer-provided insurance an appeal it would never have in a free society, where taxation would not distort decision-making. Moreover, the system creates an incentive to extend "insurance" to include noninsurable events simply to take advantage of the tax preference for noncash compensation. Today pseudo-insurance covers screening services and contraception, which of course are elective. (This does not mean they are trivial, only that they are chosen and are not happenings.)

∞

February 19, 2015 07:17 AM

By Joe Martin in Politics

Imagine that there are two providers of the same service. Their quality and timeliness are comparable. However, one provider charges significantly more than the other. In a normally functioning market, you would expect that the more expensive provider would have to significantly change its cost structure to stay in business.

What if the more expensive provider argued that it had higher overhead, and therefore needed and deserved to be paid more? He would be laughed out of the marketplace. Yet, this is exactly what happens in Medicare. Because of different fee schedules, doctors in independent practice are paid less for the same procedure than hospital-based outpatient facilities. Unsurprisingly, this has resulted in hospitals buying up physician practices, in order to profit from this arbitrage:

For example, Medicare pays more than twice as much for a level II echocardiogram in an outpatient facility ($453) as it does in a freestanding physician office ($189). This payment difference creates a financial incentive for hospitals to purchase freestanding physicians’ offices and convert them to HOPDs without changing their location or patient mix. For example, from 2010 to 2012, echocardiograms provided in HOPDs increased 33 percent, while those in physician offices declined 10 percent. (Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, March 2014, p. 53)

The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) has argued that the fees should be “site neutral” for many procedures. President Obama’s budget proposes to phase this in starting in 2017, and estimates savings of $29.5 billion over ten years (p. 65).

This is something I've seen a lot. A hospital buys a clinic. The clinic keeps the same doctors, seeing the same patients. Nothing about the building changes. But the cost of the medical care increases significantly just because the ownership changed. That's wrong and needs to stop. I support this piece of President Obama's budget.

∞

February 19, 2015 07:12 AM

By Joe Martin in Politics

For example, this 2010 Dartmouth Atlas Surgery Report from the Dartmouth Institute made much of the national variation in Medicare hip replacement rates in 2000-01. Noting that the rate ranged from 1.2 per 1,000 in the hospital referral area of Alexandria, Louisiana, to 6.7 per 1,000 in the hospital referral area of Boulder, Colorado, it concluded that

[b]ased on the data presented here, it appears that patients in some regions and among some populations may not be getting adequate access to the procedures, while patients in other regions and among other populations may be undergoing the procedures at higher rates than necessary.

Reaching such a conclusion from local hip replacement rates requires assuming that the U.S. population is composed of identical people identically distributed over a featureless geographic plain that is everywhere the same.

Unfortunately, the Dartmouth report failed to inform readers that the most common reason for hip replacement is osteoarthritis and that it is well known that the prevalence of primary osteoarthritis of the hip occurs at much higher rates in Caucasians than in other population groups. In 2010, the proportion of blacks or African Americans in Alexandria, Louisiana, was 57.3 percent. In Boulder, Colorado, it was less than one percent. Hip replacement rates also vary with age, comorbidities, socio-economic group, and employment history.

I did not know this. It does seem relevant to know this, before concluding that one region is doing "too many" hip replacements.

∞

February 16, 2015 08:08 AM

By Joe Martin in Politics

Part-time Staples workers are furious that they could be fired for working more than 25 hours a week.

The company implemented the policy to avoid paying benefits under the Affordable Care Act, reports Sapna Maheshwari at Buzzfeed. The healthcare law mandates that workers with more than 30 hours a week receive healthcare.

If Staples doesn't offer benefits, it could be fined $3,000 in penalties per person.

Buzzfeed spoke with several Staples workers who revealed their hours have been drastically cut over the past year. Many reported working as few as 20 hours.

Obamacare sure has been good to low-income workers, who are struggling to get by.

∞

November 09, 2013 08:12 AM CST

By Joe Martin in Politics

D. J. Jaffe taught me something that I had no idea about.

President Obama should focus any incremental expansions in social-service and health-care programs on those who need it most. Ninety percent of people with the most serious mental illness, schizophrenia, cannot work and therefore do not have private insurance — they rely on Medicaid. The new regulations will mean little to them. Medicaid reimburses states for roughly 50 percent of the cost of caring for the truly indigent. But an obscure provision of Medicaid law called the “IMD Exclusion” prevents Medicaid from reimbursing states for the care and treatment of people in state psychiatric hospitals. As a result, states bear 100 percent of the costs of state psychiatric hospitals and have learned that, by kicking people out of such institutions, they can get reimbursed by Medicaid for fifty percent of their care in the community. So kick them out they do.

A report I co-authored with lead author Dr. E. Fuller Torrey of the Treatment Advocacy Center found that, in 1955, ten years before Medicaid was enacted, there were 340 public psychiatric beds available per 100,000 Americans. In 2005, there were only 17 public psychiatric beds available per 100,000. In other words, the number of beds per capita dropped 95 percent from 1955 to 2005. We are now short over 100,000 beds for the most seriously mentally ill — and that assumes we had perfect community services, which we don’t.

That's pretty bad. If the President wants political wins, I think this is worth pushing for. It's something that seems like it would really help and—in the wake of mass shootings by mentally ill individuals—he has a good chance of getting the NRA and other groups to support it.

∞

October 19, 2012 09:43 AM CDT

By Joe Martin in Politics

Avik Roy, on a very promising development from the AMA.

At the Vice-Presidential debate last week, Joe Biden claimed that the American Medical Association sided with him, and against Paul Ryan, on the merits of the Romney-Ryan plan for Medicare reform. “Who do you believe?” exclaimed Biden. “The AMA [and] me? A guy who has fought his whole life for this? Or somebody [like Paul Ryan]?” Well, it turns out that the AMA’s key policy committee has come out in favor of premium support for Medicare, in a fashion that tracks closely with what Mitt Romney and Paul Ryan are proposing.

... The AMA Council’s report states that it came around to this view not at the behest of Republican operatives or candidates, but after speaking with Bill Clinton’s former budget chief, Alice Rivlin, who along with Paul Ryan proposed a version of this plan. “Dr. Rivlin emphasized that defined contribution amounts should be sufficient to ensure that all beneficiaries could afford to purchase health insurance coverage, and that private health insurance plans should be subject to regulations that protect patients and ensure the availability of coverage for even the sickest patients.”

∞

October 19, 2012 08:00 AM CDT

By Joe Martin in Politics

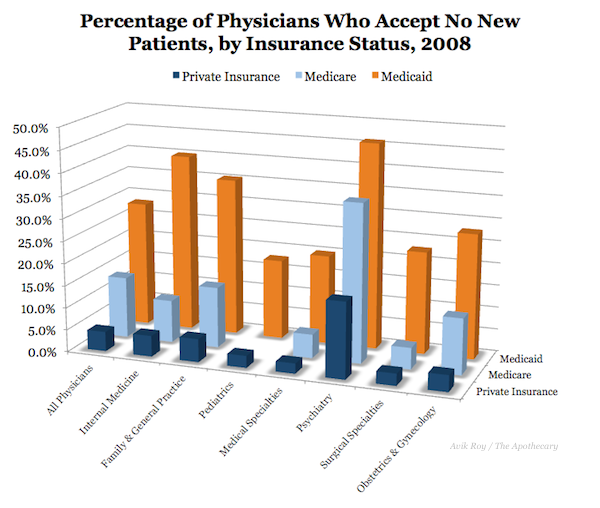

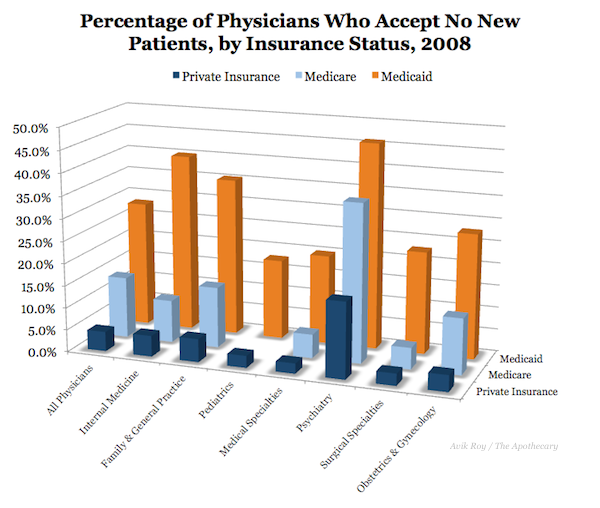

Just because you have a piece of paper that says you have “health insurance” doesn’t mean that you can see a doctor when you need to.

There are three major forms of health insurance in America: Medicare, our government-sponsored program for the elderly; Medicaid, our government-sponsored program for the poor; and private insurance for most everyone else. As I have described extensively on this blog, it’s much harder to get a doctor’s appointment if you’re on Medicaid than if you have private insurance, because Medicaid pays doctors so little that doctors can’t afford to see Medicaid patients. This, in turn, leads patients on Medicaid that are at best no different than being uninsured, and in many cases even worse.

∞

October 16, 2012 11:50 AM CDT

By Joe Martin in Politics

How do you debate a guy who makes everything up on the fly?

I’d like to discuss the substance of the debate on health care and tax reform, where Joe Biden told one whopper after another in an attempt to help President Obama regain lost campaign momentum.

I was arguing with the TV when VP Biden was making up these facts. The more you know about policy, the more of a buffoon the VP is.

- Contra Biden, Senator Ron Wyden does still support the Wyden-Ryan Medicare reform plan.

- Contra Biden, the CBO determined that Medicare wouldn't save any money by negotiating drug prices .

- Contra Biden, Obamacare did cut $716 billion from Medicare and probably will cause 1 in 6 hospitals to go under and cause 15% of Medicare doctors to stop taking Medicare patients.

- Contra Biden, 7.4 million seniors are expected to lose access to Medicare Advantage once the Obamacare changes are fully phased in, in 2014.

∞

October 16, 2012 08:00 AM CDT

By Joe Martin in Politics

Dr. Rob Lamberts isn't going to deal with third party payments anymore.

No, this isn’t my ironic way of saying that I am going to change the way I see my practice; I am really quitting my job. The stresses and pressures of our current health care system become heavier, and heavier, making it increasingly difficult to practice medicine in a way that I feel my patients deserve. The rebellious innovator (who adopted EMR 16 years ago) in me looked for “outside the box” solutions to my problem, and found one that I think is worth the risk. I will be starting a solo practice that does not file insurance, instead taking a monthly “subscription” fee, which gives patients access to me.

∞

October 12, 2012 12:09 PM CDT

By Joe Martin in Politics

Ross Levatter offers a vision of what truly free market healthcare might look like. It's radically different from what we have now, but it's the system I, personally, want to have.

... Many healthcare items–from CTs to cholecystectomies–are clearly priced, and people compare prices and shop for quality as well. You can look up surgeons and radiologists on the Internet, for example, and see what prior customers thought of the quality of their services. Other people choose to use a qualified middleman to recommend a local physician of high quality and reasonable price. Such middlemen advertise their services and list many reasons to use them, including the opportunity to take advantage of volume discounts and to have someone knowledgeable to guide you through the various medical options. Yet others make their own decisions, using the Internet and new software programs, just as they use software to help them make the right tax-paying decisions.

Mayo and Kaiser, among others, take strong advantage of their brand name, which signifies quality, but the competition from many other physicians makes it difficult for them to charge too much additional for “value-added.”

∞

October 11, 2012 09:43 AM CDT

By Joe Martin in Politics

A new paper from Georgetown University researchers suggests a third possible outcome: Absolutely nothing at all will happen. They looked at the three states – Maine, Georgia and Wyoming – that have passed laws allowing insurers from other states to participate in their markets. All have done so within the past two years.

So far, none of the three have seen out-of-state carriers come into their market or express interest in doing so. It seems to have nothing to do with state benefit mandates, and everything to do with the big challenge of setting up a network of providers that new subscribers could see.

Interesting. This is another argument in favor of spending out of pocket instead of purchasing healthcare through health insurance. You can negotiate and shop around immediately. You don't have to wait for an insurance company to set up a network and then pay them.

∞

October 11, 2012 08:00 AM CDT

By Joe Martin in Politics

Economists agree on theoretical grounds and have shown empirically that all contributions toward premiums—those made by employers and workers alike—are forgone wages. In other words, wages are lower by exactly the amount of the premium, even when the employer seems to pay it. What’s going on here is that employers are shifting compensation from wages to premiums. The preferential tax treatment of the latter encourages this.

Because wages are taxed, compensation in the form of health insurance in lieu of wages reduces government revenue. In fact, it reduces it a lot: $250 billion per year. Just to put that figure in perspective, $250 billion is almost half the Medicare budget. It is more than 3½ times the average annual cost of the Affordable Care Act’s low-income health insurance subsidies. Employer-sponsored health insurance is among the most subsidized types of health insurance in America, almost as subsidized as Medicaid.

The preferential tax treatment of employer-sponsored health insurance also encourages more generous coverage and higher health care spending. By one estimate, health spending among insured workers is 26% higher than it otherwise would be if not for the tax break.

We should get rid of the employer healthcare tax subsidy. It distorts purchasing incentives, it's a massive middle class welfare program, and it drives up the cost of healthcare. It's toxic and it needs to go. (McCain's healthcare plan would have accomplished that. The Obama campaign blatantly lied about it for 6 months and we got Obamacare instead. I'm still angry about that.)

∞

October 08, 2012 02:59 PM CDT

By Joe Martin in Politics

John Goodman links to a recent (gated) study from the Health Affairs Blog.

We examined both quality and actual medical costs for episodes of care provided by nearly 250,000 U.S. physicians serving commercially insured patients nationwide. Overall, episode costs for a set of major medical procedures varied about 2.5-fold, and for a selected set of common chronic conditions, episode costs varied about 15-fold…there was essentially no correlation between average episode costs and measured quality across markets.

That indicates to me that there is a lot of room for patient's to bargain for healthcare and push for lower prices. If more patients spent their own money, they'd do so. And, in so doing, they'd lower their own healthcare costs and the costs of the overall healthcare system.

∞

October 07, 2012 10:54 AM CDT

By Joe Martin in Politics

Today’s New York Times features an opinion piece by J.D. Kleinke of the conservative American Enterprise Institute. Kleinke’s thesis is that ObamaCare’s conservative opponents should stop complaining. “ObamaCare is based on conservative, not liberal, ideas.”

If one defines conservative ideas as those that emphasize free markets and personal responsibility, there is zero truth to this claim.

Michael Cannon goes on to elaborate and then concludes with:

Even if one adopts the more forgiving definition that conservative ideas are whatever ideas conservatives advocate, there still isn’t enough truth to sustain Kleinke’s point. Yes, the conservative Heritage Foundation trumpeted ObamaCare’s regulatory scheme from 1989 until around the time a Democratic president endorsed it. But as National Review‘s Ramesh Ponnuru writes, accurately, “The think tankers were divided, with the Heritage Foundation an outlier. It was an outlier, too, in the broader right-of-center intellectual world.”

∞

October 07, 2012 08:00 AM CDT

By Joe Martin in Politics

John Goodman talks about how HSA's help customers save money and help lower costs for the overall healthcare system. Too bad the Obama administration, through Obamacare, wants to get rid of HSAs.

Megan Johnson, a self-employed single mother in Dallas, had severe pains in her side and back, just below the ribs. Her doctor said it was possibly kidney stones, but a CT scan would be necessary to confirm the diagnosis. Megan's doctor gave her the name of an outpatient radiology department near her home. A call to the hospital revealed her share of the cost would be more than $2,800. Because Megan's health insurance had a $5,000 deductible, she decided to ask some questions: Do I really need this? Is it less expensive anywhere else?

A quick search of HealthcareBlueBook.com confirmed a reasonable price for an abdominal CT scan was about $800 - not $2,800. More online research identified dozens of medical imaging centers - including one next to the doctor's office. The insurance company negotiated price was $407 - a fraction of the initial price the hospital quoted. Megan was able to save nearly $2,400 by simply doing a little research online.

∞

October 06, 2012 07:49 PM CDT

By Joe Martin in Politics

Former "car czar" Steven Rattner, fresh off of "rescuing" GM, is in favor of healthcare rationing by government bureaucrat.

We need death panels.

Well, maybe not death panels, exactly, but unless we start allocating health care resources more prudently — rationing, by its proper name — the exploding cost of Medicare will swamp the federal budget.

This is the inevitable result of third-party payment: some paper pusher will arbitrarily cut off care once you've "had enough". Or we can move back to buying healthcare like we buy everything else in life: paying for healthcare out of a mix of savings and insurance, shopping for the lowest price, and taking responsibility for deciding what is and isn't necessary. There is no middle ground here.

I know which way I want to go and it's not through rationing by a board of government "specialists".

∞

October 05, 2012 03:31 PM CDT

By Joe Martin in Politics

John Goodman writes about something that will be a big problem, as medical knowledge increases. We're increasingly finding out that different people respond differently to the same treatment, depending on their genetics and the DNA of whatever is attacking them. As our knowledge about these differences increases, we will increasingly have individualized treatments.

Everything about ObamaCare — from its emphasis on pilot programs and demonstration projects to its faith in “evidence-based care” — is all about standardization. It’s about treating all patients with the same condition the same way. It’s about herd medicine. It’s about cookbook medicine. It’s about assembly line medicine. It’s as different from personalized care as different can be.

Unless we make large scale reforms to our existing regulations, we will increasingly end up knowing how to treat someone's condition yet it will illegal for the doctor to deviate from the standardized treatment in order to apply the personalized care that the patient needs.

∞